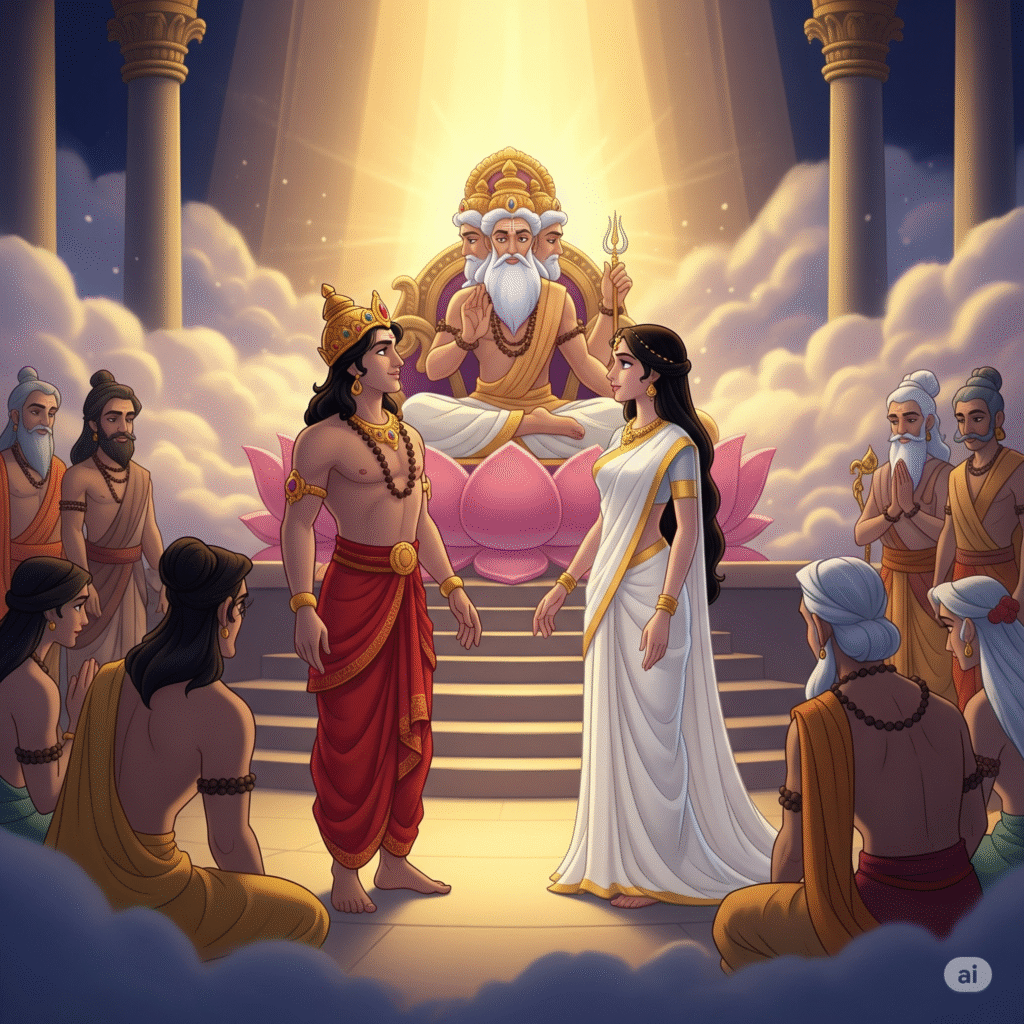

Maharaja Pandu was once roaming a vast forest teeming with deer and serpents. Pandu was lost in the thrill of the chase. He suddenly spotted a buck, deeply engrossed in a private moment of love with his doe. In that intimate instant, the King’s bow rose, without a moment’s hesitation, Pandu released five sharp, swift arrows with golden feathers, binding the loving pair. But this was no ordinary kill. The buck was, in reality, Kindama, a Mahatejasvi Rishi-putra , who was uniting with his wife, who had taken the form of a doe. Struck by the arrows, the Rishi-son fell to the earth, wailing in a human voice. His senses were scattered, his agony profound.

“O King!” he cried. “Even those men who are blind with desire and rage, devoid of wisdom, and addicted to sinful deeds, abstain from such cruel acts! You are born in the chief family of the Kshatriyas, yet how did your intellect stray from Dharma , yielding to lust and greed?” Pandu defended his actions, stating that hunting was the sanctioned duty of a king, a path followed even by great Rishis like Agastya. It was his Kshatriya-Dharma. “I do not lament that you kill the deer. I lament that you should have taken pity and waited for us to conclude our act of union. What wise man would strike down a creature fulfilling its urge for procreation in the solitude of the woods?” said the dying Maharishi. The Rishi, killed in the moment of his greatest joy and deepest vulnerability, uttered the devastating curse that marked Pandu’s soul and sealed the fate of his lineage: “You have cruelly slain a man and a woman who were engrossed in the act of procreation. You, too, O Pandu, shall find death the very moment you are united with your beloved wife in the same act, overcome by lust!” Having spoken these terrifying words, Rishi Kindama, consumed by grief, gave up his life.

The curse of Rishi Kindam ripped the veil of illusion from the King’s eyes. The swiftness of the divine judgment struck him deeper than any arrow. As the great ascetic died in the form of the wounded deer, Pandu stood frozen, utterly consumed by regret. Staring at the lifeless bodies, Pandu was engulfed by the truth of his own weakness. He lamented to himself , “Alas, how pitiful that even men born into the highest, most virtuous lines lose their Viveka (discernment) and fall into deep darkness simply because they cannot control their own hearts! The trap of Kama (lust) steals wisdom. My own father, Vichitravirya, died young, his life cut short by the very same unrestrained desires.” He recognized his own downfall as a lineage defect, noting that even though he was born from the pure union sanctioned by Vyasa, his obsession with the chase proved his undoing. He felt the gods had abandoned him because of his “evil policy” (A-niti).

The curse became Pandu’s unexpected catalyst for ultimate liberation. He made a fierce, profound decision—the pursuit of Moksha (salvation) was now his only path to welfare. The bonds of family and kingdom, which had once defined his life, now felt like the greatest source of sorrow. He resolved to follow the arduous path of his father, Vyasa, adopting the highest discipline to cleanse his sin. He sought neither blessing nor insult. He sought only the dissolution of the ego, resolving to be free from all duality (Dvandva), roaming like the wind until his very body dissolved on the path to fearless liberation.

Seeing their husband, the mighty King, transformed into a desolate ascetic before their eyes, Kunti and Madri stood firm. When Pandu commanded them to return to Hastinapur to tell his family he had become a Sannyasi, they spoke with quiet, unyielding power: “O Lord of Bharatas, there are other Ashramas (stages of life) where you can perform your great penance, and still keep us, your Dharma-patnis, by your side! If you abandon us, we will certainly give up our lives this very day!” Their fidelity was not driven by desire for comfort. They declared they would accompany him, practicing strict control over all their senses and desires. Moved by their devotion, Pandu yielded. He chose the Vanaprastha Ashrama (Forest Dweller) instead of Sannyasa. He stripped himself of all royal wealth and ornaments and distributed everything to the Brahmins, and commanded his servants to take the remaining treasure back to Dhritarashtra.

With their bark garments, matted hair, and meager diets of roots and fruits, King Pandu, Kunti, and Madri embraced their new, difficult life. They journeyed far, crossing the Nagashata and Kalakuta mountains, finally settling on Shatashringa (The Hundred-Peaked Mountain), where they dedicated themselves to deep, punishing penance.

Pandu’s tragedy is a devastating lesson on the power of indulgence versus the power of intention**.** Pandu wasn’t a cruel man; he simply acted on instinctual desire (Kama and Vyasan – Addiction to the hunt). His defense was: “This is my Dharma as a King.” The Rishi’s counter-argument exposed the hollowness of his claim: True Dharma demands Viveka and Daya (Discernment and Compassion). Pandu’s error was not the act itself, but the timing and the lack of consideration for the life he was destroying. He was so wrapped up in his own pleasure that he violated the sanctity of another’s moment of creation. We often use “I deserve this,” “It’s my break,” or “It’s my job” to justify actions that lack compassion or disregard a critical consequence. Uncontrolled desire, even for a socially acceptable activity, can lead to absolute renunciation. The universe forces us to give up everything when we fail to govern our senses in time. Pandu’s exile was the price for his unexamined pleasure.

Journaling Prompts

- Pandu’s tragedy shows that a moment of uncontrolled desire can derail a lifetime of purpose. What is the “little indulgence” in your life that you suspect could lead to a major downfall if left unchecked?

- The curse forced Pandu into asceticism, which he eventually embraced. Can you think of a time when a major setback or ‘curse’ actually forced you on to a better, more spiritual path?

- Pandu’s decision to embrace exile was an act of extreme humility. What attachment (possession, status, or desire) would be the hardest for you to willingly renounce?