There are times in a nation’s story when everything flows—like a river that knows its path. When skies rain on time, when fields yield more than asked, and when merchants thrive and temples ring with chants. It was one such time in Hastinapura. Under Bhishma’s wise rule, the Kuru kingdom flourished. Crops ripened in golden abundance, artisans and merchants were skilled and prosperous, and not a soul knew the meaning of theft or deceit. Even the animals, birds, and forests seemed to live in contentment. Dharma wasn’t just an idea; it was a way of life.

Bhishma had raised the three sons of Vichitravirya—Dhritarashtra, Pandu, and Vidura—as if they were his own. He saw to their every samskara, their education, and their rigorous training in scriptures, philosophy, warfare, and statesmanship. Each was unique. Dhritarashtra—stronger than any man. Pandu—unmatched in archery and battle. Vidura—wise, reflective, and deeply righteous.

As they grew into men, a question returned to the forefront of Bhishma’s mind—the continuation of the Kuru line. It was time to find brides, not just for companionship, but for legacy. Among the names that came to Bhishma’s ears were three princesses: Pritha (Kunti), the virtuous daughter of Shurasena and foster daughter of Kuntibhoja. Gandhari was the devout daughter of King Subala of Gandhara. And Madri, daughter of the Madra king.

Bhishma decided to approach Gandhara first. He had heard something unusual—Gandhari had pleased Lord Shiva through her penance and had been granted the boon of a hundred sons. For a dynasty seeking its future, this was a divine sign. But when King Subala heard that Dhritarashtra, the groom-to-be, was blind, he hesitated. Not because of prejudice, but because of uncertainty. Yet after much thought of the Kuru dynasty’s standing, its dharmic rule, and Bhishma’s reputation, he gave his word.

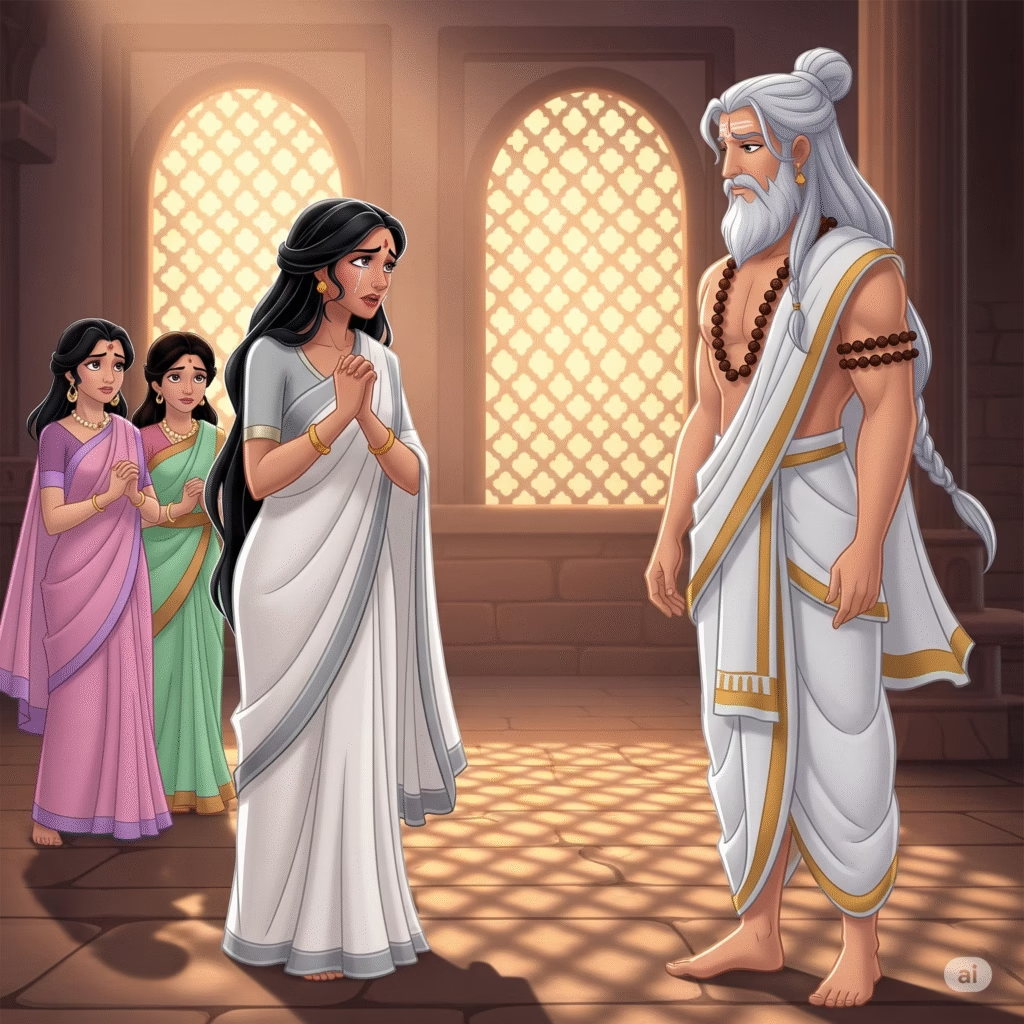

When Gandhari came to know that her future husband could not see, she did something that still echoes in the world. She took a silken cloth, folded it many times, and tied it over her own eyes. Not out of protest. Not out of submission. But out of an intense sense of pativrata dharma—if he shall not see the world, neither shall I. She would live her life not just beside her husband but in his darkness, by choice. Her brother Shakuni accompanied her to Hastinapura and gave her hand to Dhritarashtra. Bhishma honoured the alliance with generosity and grace. The marriage was completed with solemn rituals, and Gandhari’s presence filled the palace with happiness.

She would never look upon the world again, but the world would not stop looking at her. She became a queen, but more than that—a living vow. A quiet revolution draped in silk.

Gandhari’s choice was not imposed. It was her sankalpa. Her world went dark so she could walk beside her husband in true oneness. In doing so, she became more than a wife—she became an embodiment of resolve. But was it dharma to give up one’s light for another’s darkness? Or was it fear of disobedience, pressure of duty, or an inherited script she felt compelled to follow? And here lies our inner Kurukshetra. Sometimes we shut our eyes not out of loyalty, but out of fear—fear of seeing, of knowing, of standing out. But dharma is not blind. It is aware. It questions. It acts consciously.

The fear of outshining her husband. This single line rips through centuries of silent compromises. It may be wrapped in the silk of loyalty, but beneath it—yes, perhaps—was fear. Not just Gandhari’s. But every woman was taught not to rise too high, not to shine too bright. And every man’s, too, who was taught that being outshone is a threat to his worth. We often glorify such acts of self-sacrifice. But sometimes, what we call dharma is simply well-dressed fear. Fear of being questioned. Fear of unsettling the power balance. Fear of walking alone. And in that fear, silently, unknowingly, we create a world that mirrors our shackles. A world where no one is truly free. A world where silence is virtue, and dimming oneself is wisdom. And later in the story, you will see how fear ties Gandhari’s hands.

But then comes the inner Kurukshetra. That moment when we must ask: Is it truly virtuous to dim our light? Or is it more dharmic to let all lights shine equally, no matter how blinding?

Journaling Prompt

- Have you ever closed your eyes to a truth out of loyalty?

- Was it your choice—or someone else’s?