Vichitravirya was dead. No heirs. No future. No king. And Bhishma stood still, resolute in his vow, yet burning in the fire of helplessness. The palace air was heavy, but not with grief or sorrow. But with the crushing absence of a future. Satyavati watched her dynasty vanish, inch by inch, like a lamp gasping in the wind. And then, she did something no queen had done before her—she opened the doors of her past.

Bhishma, still, quiet, and duty-bound, sat before her. Satyavati looked at him not as her son, but as a pillar—the last standing one—of the Kuru lineage. She began: “Son, as suggested by you, for the sake of this lineage, we should call a wise Brahmin… one who can give sons to Vichitravirya’s widows as even rain doesn’t fall in the kingdom without a king.” Then her voice trembled. She smiled faintly, like someone reopening an old wound. She confessed a truth that had lived inside her longer than her crown. “There is someone. A Brahmin. A sage. A man whose seed I already carry…“

Long ago, she was not Satyavati, the queen. She was Matsyagandha—the daughter of a fisherman, whose boat was her only inheritance. One dusky evening, Sage Parashara arrived at the banks of the Yamuna and stepped into her boat. She ferried him. But he carried more than himself—he had desire, prophecy, and a strange destiny. On that lonely ride across the water, he looked at her with eyes not of lust, but of purpose. He said, “You are meant for more. Come with me.” She hesitated. She was young. She was scared. She feared her father’s wrath. She feared her shame. But she also feared refusing a sage’s command. And then, Parashara offered her something no woman had ever received: her virginity would remain intact, her fragrance would become divine(because she smelt like fish) and their son would be born instantly and leave as swiftly.

In a thick fog that the sage summoned, hidden from every eye of the world, the boat became the place of creation. From her womb, in an instant, emerged a dark-skinned, fierce-eyed boy—Krishna Dwaipayana, who later was called Ved Vyasa because he divided the Vedas into four parts. She never raised him. He looked at her once and said, “Mother, whenever you need me, call me.” And he vanished. Since that day, Satyavati had walked as if a river flowed within her—a past that no one knew, a secret that was never shame but was waiting for purpose. And now, that moment had come. Satyavati had never felt guilt for her past—only the weight of its timing. She didn’t hide it to protect herself but to protect others from what they were not yet ready to understand. There comes a time in each life when we must call our buried truths forward. Not all secrets are sins. Some are seeds—meant to grow only when the world is ready.

When Bhishma heard the story, he did not flinch. He folded his hands, bowed his head, and said with the humility only a great man knows, “Mother, what you have spoken is not only lawful—it is good. It is for the welfare of our lineage.” He gave his full consent. And in that moment of silent agreement between mother and son, the fate of the Mahabharata was realigned. Satyavati, in that moment, remembered her son. That’s all she did. She thought of him. And he appeared. Vyasa—chanting the Vedas, glowing with austerity, born of no kingdom but of the soul—stood before her, as if he had always been near. She ran to him. Held him. Wept on his shoulders. Her tears were not just maternal—they were queenly, desperate, and relieved. She said, “My son… your brother has died. His wives have no children. Our lineage will fall. The throne is empty. Will you… help?”

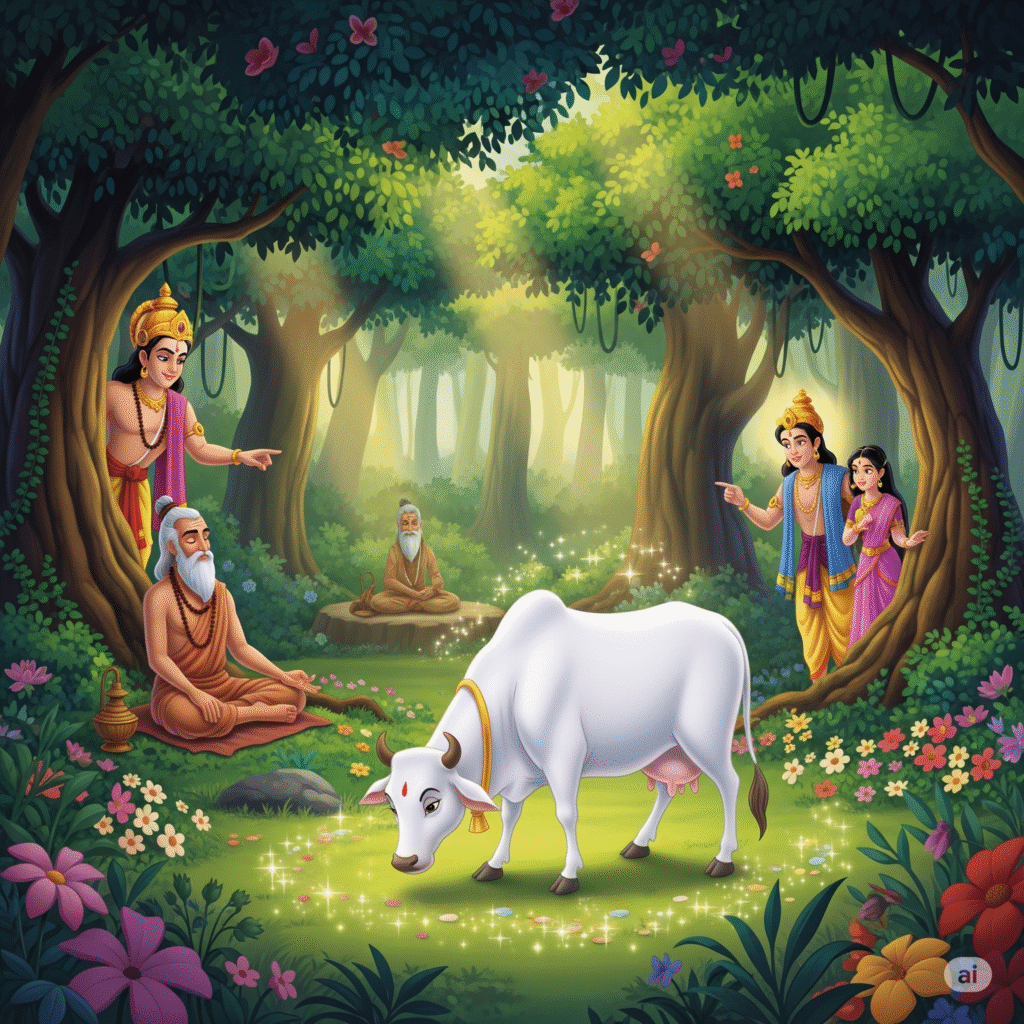

Vyasa, the knower of all dharmas, nodded: “Mother, I shall do what is right. But this is no act of pleasure. This is for dharma.” He warned: The queens must undergo a period of purity (vrata) for one full year. If that was not possible, they must accept his terrible appearance, for Vyasa had not cleaned himself in years of tapasya. His body was fierce, wild, and unkempt.

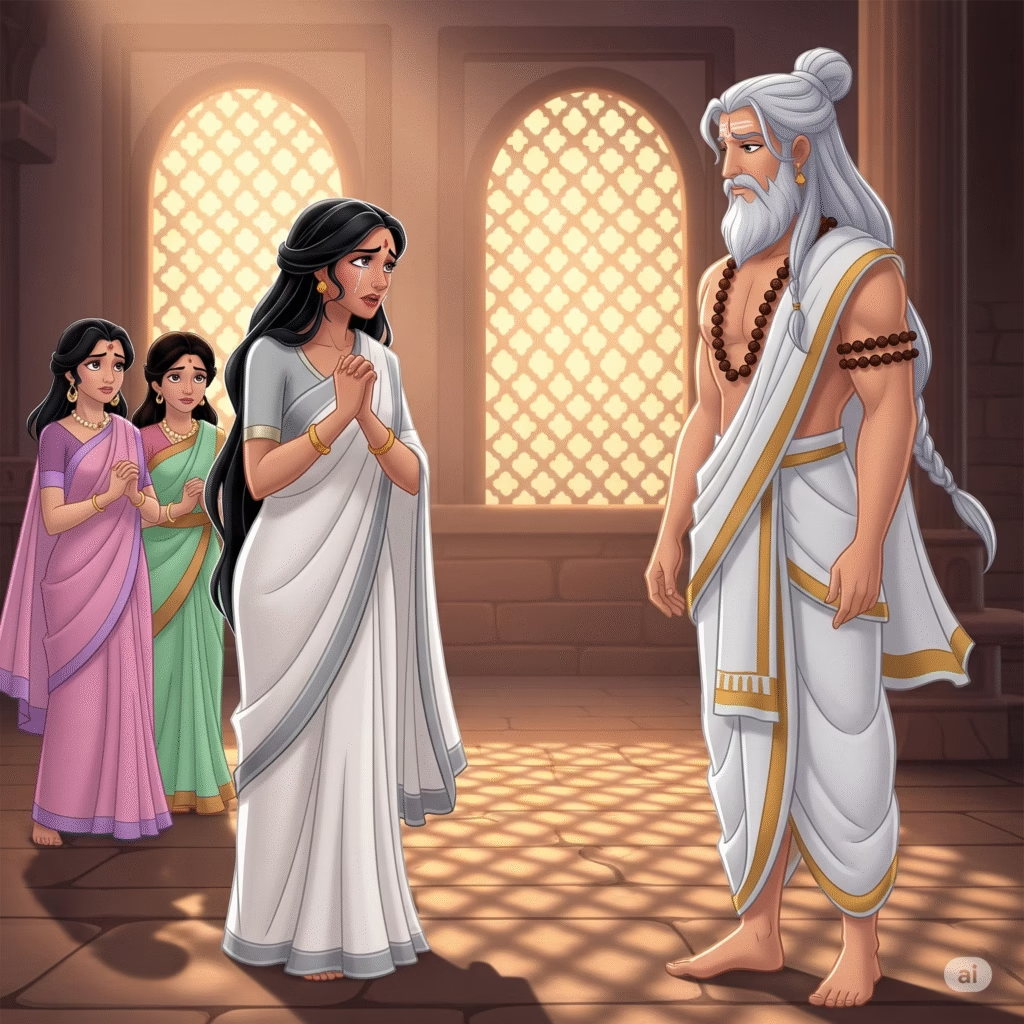

Satyavati asked him to begin immediately. The time was dire. Vyasa agreed but added, “If they cannot bear to see me, the child may be born flawed.” The first to be approached was Ambika, Vichitravirya’s elder queen. Satyavati went to her personally. She didn’t beg. She didn’t plead. She spoke in the language of dharma: “Daughter, you have the power to save a lineage. You can become the mother of kings. Will you accept this path?” Ambika hesitated. But seeing the queen’s grief, the palace’s emptiness, and the silent approval of Bhishma, she agreed. The ritual of niyoga was set to begin.

When Satyavati finally revealed her hidden truth, she wasn’t merely narrating the birth of Vyasa—she was unfolding an entire world of ancient dharma, where choices were rarely black or white. And when Bhishma gently proposed the act of niyoga, it wasn’t a plea born out of desperation, nor did desire stain it. It was a call to uphold the lineage through a path sanctioned by sacred law. The Manusmriti describes niyoga not as a physical union driven by passion, but as a solemn, disciplined act of duty. The man chosen for niyoga was to be a self-controlled, wise Brahmana—one who would approach the widow with silent reverence, his body anointed in ghee, his voice restrained. Only one child was to be born—never a second. After the union, they were to treat each other not as lovers, but with respectful distance. This was no indulgence. This was tapasya—a ritual done not with the fire of longing, but with the fire of sacrifice. In today’s world, where consent and context matter more than ever, perhaps it is time to look deeper, not to copy, not to glorify, but to understand. What if dharma, too, was once expressed in ways we no longer have the language for?

This adhyaya doesn’t end in fireworks. It ends in the quiet beginning of something profoundly eternal. A mother summoned her son. A son obeyed his dharma. A widow stepped beyond her grief to serve a kingdom. And the great epic of the Mahabharata shifted its course.

Journaling Prompts

- What truth about yourself have you hidden, not because it is wrong, but because you feared it might be misunderstood?

- Have you ever avoided stepping into your dharma because it was emotionally uncomfortable, even if you knew it was right?